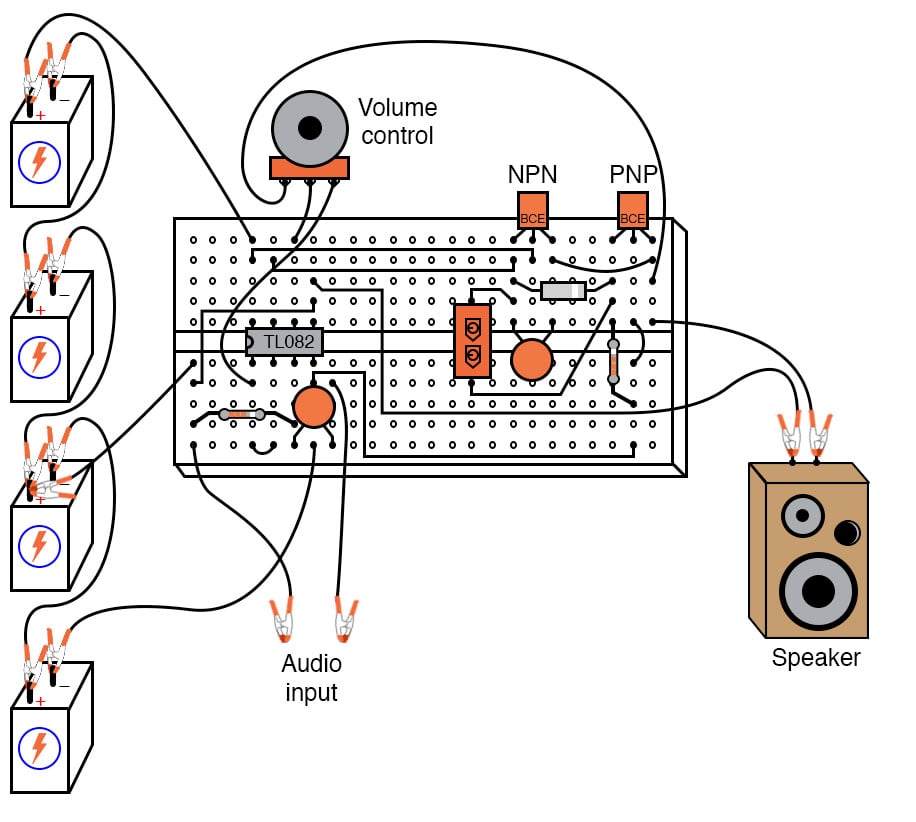

Class B audio amplifiers provide efficient power amplification of analog signals, but often at the expense of signal distortion. In this project, you will build the Class B (push-pull) audio amplifier, shown in Figure 1.

In this project, you will learn about some of the causes of audio distortion and how we can modify basic designs to minimize this distortion.

Be sure to use an op amp with a high slew rate; avoid the LM741 or LM1458 for this reason.

The closer matched the two transistors are, the better. If possible, try to obtain TIP41 and TIP42 transistors, which are closely matched NPN and PNP power transistors with dissipation ratings of 65 W each. If you cannot get a TIP41 NPN transistor, the TIP3055 is a good substitute. Do not use very large (i.e. TO-3 case) power transistors, as the op amp may have trouble driving enough current to their bases for good operation.

Step 1: This project is an audio amplifier suitable for amplifying the output signal from a small radio, tape player, CD player, or any other source of audio signals. Build the circuit shown in the circuit schematic of Figure 2 and illustrated above in the breadboard implementation of Figure 1.

Step 2: To obtain an input signal for this amplifier to amplify, connect it to the output of a radio or other audio device, as shown in Figure 3, for a mono audio plug.

Step 3 (optional): For stereo operation, two identical amplifiers must be built, one for the left channel and the other for the right channel. A stereo plug will have three signals: ground, left, and right.

This amplifier circuit also amplifies line-level audio signals from high-quality, modular stereo components. It provides a surprising amount of sound power when played through a large speaker and can be run without heatsinks on the transistors. However, you should experiment with it a bit before deciding to forego heat sinks, as the power dissipation varies according to the type of speaker used.

This particular circuit is called a Class B push-pull circuit. Most audio power amplifiers use a class B configuration, where one transistor provides power to the load during one-half of the waveform cycle (it pushes), and a second transistor provides power to the load for the other half of the cycle (it pulls). In this scheme, neither transistor remains on for the entire cycle, giving each one time to rest and cool during the waveform cycle. This makes for a power-efficient amplifier circuit but leads to a distinct type of nonlinearity known as crossover distortion.

Shown in Figure 4 is a sine-wave signal, equivalent to a constant audio tone of constant volume.

In a push-pull amplifier circuit, the two output transistors take turns amplifying the alternate half-cycles of the waveform, as illustrated in Figure 5.

The PNP transistor #1 drives the output high, while the NPN transistor #2 drives the output low.

The goal of any amplifier circuit is to reproduce the input waveshape as accurately as possible. Perfect reproduction is impossible, of course, and any differences between the output and input waveshapes are known as distortion. In an audio amplifier, distortion may cause unpleasant tones to be superimposed on the true sound. There are many different configurations of audio amplifier circuitry, each with its own advantages and disadvantages.

If the hand-off between the two transistors is not precisely synchronized, though, the amplifier’s output waveform may look something like the signal shown in Figure 6 instead of a pure sine wave.

Here, distortion results from the fact that there is a delay between the time one transistor turns off and the other transistor turns on. This type of distortion, where the waveform flattens at the crossover point between positive and negative half-cycles, is called crossover distortion.

One common method of mitigating crossover distortion is to bias the transistors so that their turn-on/turn-off points actually overlap so that both transistors are in a state of conduction for a brief moment during the crossover period (Figure 7).

This form of amplification is technically known as class AB rather than class B because each transistor is on for more than 50% of the time during a complete waveform cycle.

The disadvantage to doing this, though, is increased power consumption of the amplifier circuit. When both transistors are conducting, there is current conducted through the transistors that are not going through the load but are merely being shorted from one power supply rail to the other (from +V to -V).

Not only is this a waste of energy, but it dissipates more heat energy in the transistors. When transistors increase in temperature, their characteristics change (Vbe forward voltage drop, β, junction resistances, etc.), making proper biasing difficult.

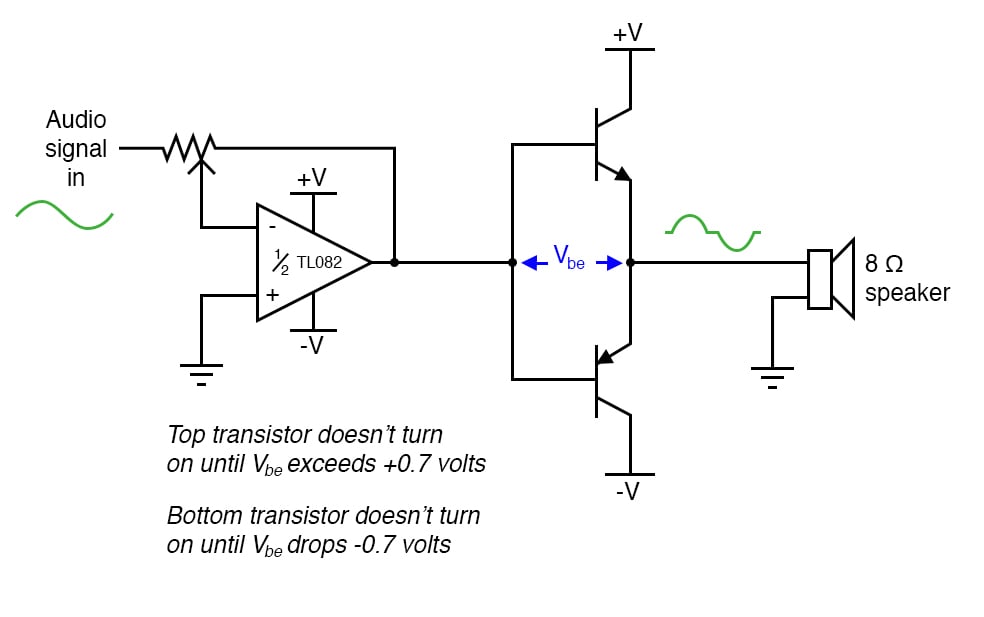

In this experiment, using the circuit of Figure 2, the transistors operate in pure class B mode. That is, they are never conducted at the same time. This saves energy and decreases heat dissipation but lends itself to crossover distortion. The solution taken in this circuit is to use an op amp with negative feedback to quickly drive the transistors through the dead zone producing crossover distortion and reducing the amount of flattening of the waveform during the crossover.

The first (leftmost) op amp, shown in the schematic diagram of Figure 2, is nothing more than a buffer (voltage follower). A buffer helps to reduce the loading of the input capacitor/resistor network at the audio signal input. The series capacitor filters out any DC bias voltage from the input signal, preventing any DC voltage from becoming amplified by the circuit and sent to the speaker, where it might cause damage.

Without the buffer op amp, the capacitor/resistor filtering circuit reduces the low-frequency (bass) response of the amplifier and accentuates the high-frequency (treble).

The second op amp functions as an inverting amplifier with the gain controlled by the 10 kΩ potentiometer. This does nothing more than provide volume control for the amplifier. Usually, inverting op amp circuits have their feedback resistor(s) connected directly from the op amp output terminal to the inverting input terminal, as illustrated in Figure 8.

If we were to use the resulting output signal from this inverting amplifier circuit to drive the base terminals of the push-pull transistor pair, though, we would experience significant crossover distortion. As shown in Figure 9, there would be a dead zone in the transistors’ operation as the base voltage went from +0.7 V to -0.7 V.

Step 4 (optional): If you have already constructed the amplifier circuit in its final form, you may simplify it to this form and listen to the difference in sound quality. If you have not yet begun constructing the circuit, the schematic diagram shown above would be a good starting point. It will amplify an audio signal, but it will sound horrible!

The reason for the crossover distortion is that when the op amp output signal is between +0.7 V and -0.7 V, neither transistor will be conducting. The output voltage to the speaker will be 0 V for the entire 1.4 V span of the base voltage swing. Thus, there is a zone in the input signal range where no change in speaker output voltage will occur.

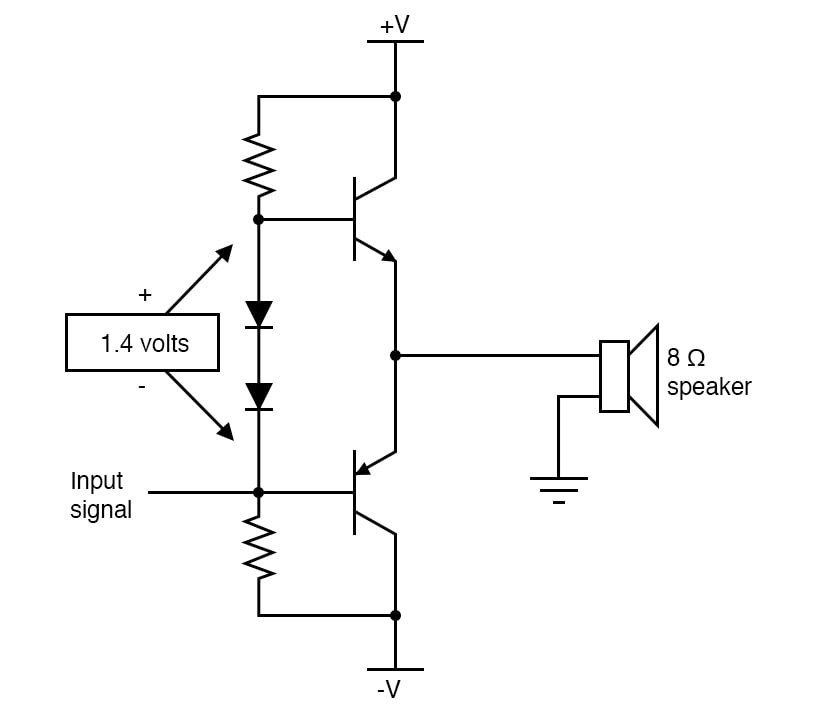

Here is where intricate biasing techniques are usually introduced to the circuit to reduce this 1.4 V gap in transistor input signal response. Usually, something like adding two diodes, as illustrated in Figure 10, is done.

The two series-connected diodes will drop approximately 1.4 V, equivalent to the combined Vbe forward voltage drops of the two transistors. With this biasing, each transistor is just on the verge of turning on when the input signal is zero volts. This eliminates the 1.4 V dead signal zone that existed before.

Unfortunately, though, this solution is not perfect. As the transistors heat up from conducting power to the load, their Vbe forward voltage drops will decrease from 0.7 V to something less, such as 0.6 V or 0.5 V. The diodes, which are not subject to the same heating effect because they do not conduct any substantial current, will not experience the same change in forward voltage drop.

Thus, the diodes will continue to provide the same 1.4 V bias voltage even though the transistors require less bias voltage due to heating. The result will be that the circuit drifts into class AB operation, where both transistors will be in a state of conduction for part of the time. This, of course, will result in more heat dissipation through the transistors, exacerbating the problem of forward voltage drop change.

A common solution to this problem is the insertion of temperature-compensation feedback resistors in the emitter legs of the push-pull transistor circuit, as demonstrated in Figure 11.

This solution doesn’t prevent simultaneous turn-on of the two transistors but merely reduces the severity of the problem and prevents thermal runaway. It also has the unfortunate effect of inserting resistance in the load current path, limiting the output current of the amplifier.

The solution opted for in this experiment is one that capitalizes on the principle of op amp negative feedback to overcome the inherent limitations of the push-pull transistor output circuit. We'll use one diode to provide a 0.7 V bias voltage for the push-pull pair, as shown in Figure 12.

This is not enough to eliminate the dead signal zone, but it reduces it by at least 50%. Since the voltage drop of a single diode will always be less than the combined voltage drops of the two transistors’ base-emitter junctions, the transistors can never turn on simultaneously, thereby preventing class AB operation.

Next, to help eliminate the remaining crossover distortion, the feedback signal of the op amp is taken from the output terminal of the amplifier (the transistors’ emitter terminals), as demonstrated in Figure 13.

The op amp’s function is to output whatever voltage signal it has to to keep its two input terminals at the same voltage (0 V differential). By connecting the feedback wire to the emitter terminals of the push-pull transistors, the op amp has the ability to sense any dead zone where neither transistor is conducting and output an appropriate voltage signal to the bases of the transistors to quickly drive them into conduction again to keep up with the input signal waveform.

This requires an op amp with a high slew rate (the ability to produce a fast-rising or fast-falling output voltage), which is why the TL082 op amp was specified for this circuit. Slower op amps such as the LM741 or LM1458 may not be able to keep up with the high dv/dt (voltage rate-of-change over time) necessary for low-distortion operation.

The final circuit is shown in Figure 14, where a couple of capacitors are added to this circuit to bring it into its final form.

A 47 µF capacitor connected in parallel with the diode helps to keep the 0.7 V bias voltage constant despite large voltage swings in the op amp’s output. A 0.22 µF capacitor connected between the base and emitter of the NPN transistor helps reduce crossover distortion at low-volume settings.

Learn more about the fundamentals behind this project in the resources below.

Textbook:

Worksheets:

In Partnership with Siemens Digital Industries Software

by Aaron Carman