E-Waste: The Seedy Underbelly of PCB Disposal

Over a decade past the first alarm bells of the effects of electronic and electrical waste, e-waste is still a major blight in the electronics industry.

Electrical engineers are used to seeing the early stages of a device's life. But have you ever considered your PCB's end of life? Once a user discards it, where does it land? How is it disposed of?

With the sharp demand for electronics comes a steep increase of electronic waste, otherwise known as e-waste. Even if engineers aren't the ones responsible for where their designs end up, it's important to stay informed on how the materials EEs work with every day affect the 50 million tons of e-waste produced a year.

What Is E-Waste?

A broad definition of e-waste is any discarded material with a plug, electric cord, or battery that comes from an electronic device used in households, businesses, and governments. E-waste can contain precious metals such as gold, copper, and nickel along with rare materials like indium and palladium.

According to a UN report on e-waste, an estimated 7% of the world’s gold may be contained in e-waste.

Image used courtesy of the Basal Action Network (BAN)

The metals in e-waste can be recovered, recycled, and used as secondary materials for new goods, but this process can come at a great challenge since electronic products can contain more than 1,000 different substances. There are regulations in place to address some of the harmful chemicals in electronic components—notably, the EU established the RoHS standard and several US states have their own directives. But not all international companies choose to comply with these regulations when they aren't compelled to do so.

Perhaps the material makeup of e-waste wouldn't be such a concern if it weren't for the fact that more and more is being produced, by the tons, every day.

A "Tsunami of E-Waste"

Currently, the world produces up to 50 million tons of e-waste a year and, according to a report from the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE) and the UN E-Waste Coalition, that number is expected to reach 120 million tons per year by 2050 if current trends continue.

In 2017, more than 44 million tons of electronic and electrical waste was produced—that’s more than thirteen pounds for every person living on our planet. The annual value of global e-waste is estimated at over $62.5 billion, greater than the GDP over 123 countries. With e-waste as the fastest-growing waste stream in the world, the UN has called this issue a “tsunami of e-waste.”

What About Electronics Recycling?

E-waste recycling is touted by groups and institutions such as the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Basel Action Network (or BAN), which seeks to reduce the trade of toxic waste.

But how much of e-waste is actually recycled?

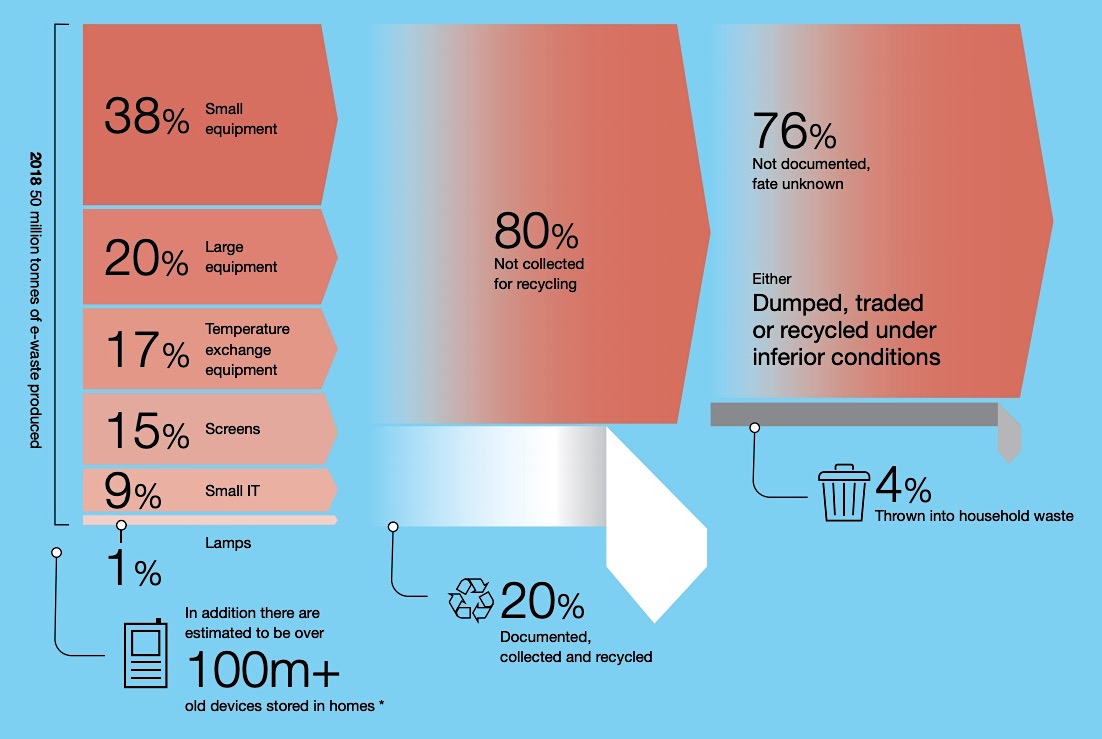

In their 2017 report, the Global E-waste Monitor claimed that only 20% of e-waste is documented, collected, and recycled while 4% is thrown into household waste. Little data exists on what happens to the other 74%, but the report posits that much of it may end up in landfills, traded, or recycled improperly.

Visualization of the percentage of e-waste that is properly recycled. Image used courtesy of the Global E-waste Monitor

One reason that e-waste isn’t properly recycled is that it costs manufacturers less to use new raw material than recycled material. Many recycling centers are funded by local governments and thus sell any materials they receive to balance their budget.

However, when raw materials are cheaper than recycled materials, recycling centers can choose to refuse waste—and many have chosen to refuse e-waste. This has been seen in various states such as North Carolina, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Texas.

There are currently 25 states with state-enacted e-waste programs. Image used courtesy of the National Conference of State Legislatures

In places where electronics recycling is not available, e-waste can exacerbate air, water, and soil pollution because toxic elements such as arsenic, cadmium, chromium, mercury, and lead are not being disposed of properly.

In India, there have been recorded informal recycling sites where PCBs are burned. Combustion from burning e-waste can create fine particulate pollution, which is linked to pulmonary and cardiovascular disease. Overall, the pollution from improper disposal of e-waste can be detrimental to human health, with the potential to be carcinogenic.

Unfortunately, there have also been various exposes over the years—from VICE to PBS to National Geographic—showing that these recycling efforts are often more valuable for their good intentions more than their effectiveness. Various glimpses into tracking e-waste shipments have yielded data suggesting that companies claiming to process recycled e-waste often ultimately dump them in landfills.

Part of the issue, according to the Global E-waste Monitor, is that better education, data, and monitoring is required to ensure better e-waste policies and more effective action.

E-waste is a daunting issue to address. How do you as an engineer think about e-waste in your day-to-day design work? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Featured image used courtesy of The Global E-Waste Statistics Partnership.

On the plus side, the typical electronic device has become much smaller resulting in less waste per device. This includes consumer products (cell phones, etc) as well as individual components. Compare the Motorola 68000 processor in a megalithic 64 pin DIP package to the more powerful and faster ARM processors in their tiny packages that are ubiquitous today.

.

CRT televisions had giant energy intensive (both in manufacture and during use) tubes that, in addition, also had a drop of mercury. We’ve eliminated most of these and are not making new ones. LCD televisions formerly used fluorescent lamps for backlighting which contained a similar amount of mercury. Today most units are LED backlit, eliminating the mercury.

.

ROHS has been around for nearly 30 years. It has been required in European products for that whole time. It hasn’t been required in the US, but most product developers have signed on to using lead-free solder and eliminating cadmium and other hazardous chemicals noted in the ROHS requirements.

.

At some point, it’s going to be financially viable to refine gold from electronics waste. This will likely be in the form of treating the waste similarly to extracting gold from ore, grinding it into small pieces, chemically treating it to get the gold.